Ismaila Abubakar

Ismaila Abubakar

Department of City and Regional Planning

King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals

Dhahran, Saudi Arabia

This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it

Yusuf A. Aina

Department of City and Regional Planning

King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals

Dhahran, Saudi Arabia

This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it

ABSTRACT:

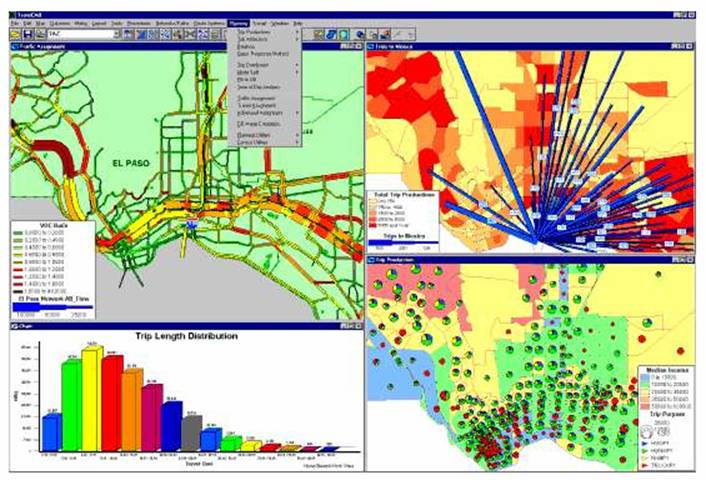

Accessibility as a relative nearness of one place to another indicates easiness of reaching destination from origin. As a spatial analytic measure, it plays a vital role for decision makers in deciding where to locate public facilities or amenities so as to maximise their usability. More accessible public facilities like parks and open spaces improve social cohesion and interaction as more people patronise them. Better accessibility to facilities also ensures economic efficiency in the use of such facilities because when they service more people, they would be more cost effective. One of such places where the location of green areas is meant to serve the above-mentioned purposes is Doha district in Saudi Arabia.

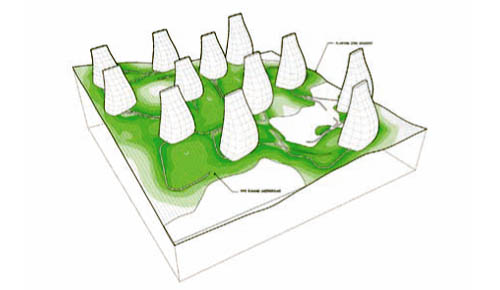

Doha is a new district in Dammam metropolitan region of Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. It is designed in grid-iron pattern with some organised green areas in contrast with the old traditional organic settlements. The District is planned by Saudi Arabian Oil Company (ARAMCO) to serve as a model to the new and traditional settlements in the country. The green areas include parks and open spaces serving as public recreation centres. But are they accessible to their intended beneficiaries?

Environment and Ecology

environment - ecology - nature - habitat - gaia - permaculture - systems - sustainability ...

GIS and Space Syntax: An Analysis of Accessibility to Urban Green Areas in Doha District of Dammam Metropolitan Area |

|||

HistoryLEED began in 1993 spearheaded by Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) senior scientist Robert K. Watson who, as Founding Chairman of the LEED Steering Committee until 2006, led a broad-based consensus process which included non-profit organizations, government agencies, architects, engineers, developers, builders, product manufacturers and other industry leaders. Early LEED committee members also included USGBC co-founder Mike Italiano, architects Bill Reed and Sandy Mendler, builder Gerard Heiber, builder Myron Kibbe and engineer Richard Bourne. As interest in LEED grew, in 1996, engineers Tom Paladino and Lynn Barker co-chaired the newly formed LEED technical committee. From 1994 to 2006, LEED grew from one standard for new construction to a comprehensive system of six standards covering all aspects of the development and construction process. LEED also has grown from six volunteers on one committee to more than 200 volunteers on nearly 20 committees and over 200 professional staff in Washington, DC. LEED was created to accomplish the following:

Green Building

Although new technologies are constantly being developed to complement current practices in creating greener structures, the common objective is that green buildings are designed to reduce the overall impact of the built environment on human health and the natural environment by:

A similar concept is natural building, which is usually on a smaller scale and tends to focus on the use of natural materials that are available locally.[2] Other related topics include sustainable design and green architecture.

Reducing environmental impactGreen building practices aim to reduce the environmental impact of buildings. Buildings account for a large amount of land use, energy and water consumption, and air and atmosphere alteration. Considering the statistics, reducing the amount of natural resources buildings consume and the amount of pollution given off is seen as crucial for future sustainability, according to EPA.The environmental impact of buildings is often underestimated, while the perceived costs of green buildings are overestimated. A recent survey by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development finds that green costs are overestimated by 300 percent, as key players in real estate and construction estimate the additional cost at 17 percent above conventional construction, more than triple the true average cost difference of about 5 percent. Goals of green building The concept of sustainable development can be traced to the energy (especially fossil oil) crisis and the environment pollution concern in the 1970s.[3] The green building movement in the U.S. originated from the need and desire for more energy efficient and environmentally friendly construction practices. There are a number of motives to building green, including environmental, economic, and social benefits. However, modern sustainability initiatives call for an integrated and synergistic design to both new construction and in the retrofitting of an existing structure. Also known as sustainable design, this approach integrates the building life-cycle with each green practice employed with a design-purpose to create a synergy amongst the practices used. The concept of sustainable development can be traced to the energy (especially fossil oil) crisis and the environment pollution concern in the 1970s.[3] The green building movement in the U.S. originated from the need and desire for more energy efficient and environmentally friendly construction practices. There are a number of motives to building green, including environmental, economic, and social benefits. However, modern sustainability initiatives call for an integrated and synergistic design to both new construction and in the retrofitting of an existing structure. Also known as sustainable design, this approach integrates the building life-cycle with each green practice employed with a design-purpose to create a synergy amongst the practices used.Green Building (MIT)

The Green Building was constructed 1962-1964. It is 21 stories tall, with a concrete facade that more or less matches the older limestone around it. The basement of the building is below sea level and connects to the MIT tunnel system. Three elevators operate in the Green Building. There are staircases on both the east and west sides of it. On the "Lower Level" (actually one story above ground level), is 54-100, a large lecture hall. The 2nd floor contains the Lindgren Library, part of MIT's library system. The Green Building is the tallest building in Cambridge. When it was built, there was a limit on the number of floors. Thus, it was designed to be on stilts and the 1st floor be 3 stories tall in order to "circumvent" this law. Currently, no building in Cambridge is allowed to be taller than the Green Building.

The GreenBuilding Programme

On this central project website, information will be updated and amanded continuously. Furthermore, you will find links to the websites of the ten National Contact Points and the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC). The GreenBuilding ProgrammeIn its Green Paper on Energy Efficiency, the European Commission (EC) identified the building sector as an area, where important improvements in energy efficiency can be realised. According to the Green Paper, the building sector accounts for more than 40% of the final energy demand in Europe. At the same time, improved heating and cooling of buildings constitutes one of the largest potentials for energy savings. Such savings would also improve the energy supply security and the EU’s competitiveness, while creating jobs and raising the quality of life in buildings. |

|||

|

|

|||

| Page 3 of 3 |

Environment and Architecture

Environment and Architecture

[Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr].

[Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr]. [Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr].

[Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr]. The Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design

The Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design

In 2004, the European Commission initiated the

In 2004, the European Commission initiated the