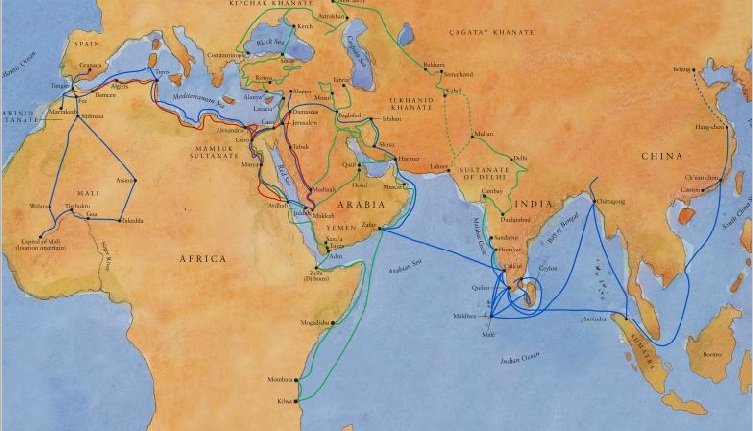

When it comes to globetrotting, even Marco Polo takes a back seat to this fourteenth-century voyageur.

In the year 1349 a dusty Arab horseman rode slowly toward the city of Tangier on the North African coast. For Ibn Battuta, it was the end of a long journey. When he left his home in Tangier 24 years earlier, he had not planned to travel distant roads all during the years that took him from young manhood to middle-age. From his mount, Ibn Battuta surveyed the white spires and homes of Tangier spreading in a crescent along the Atlantic Ocean. He tried to remember how the city had looked when he left it behind almost a quarter-century ago.

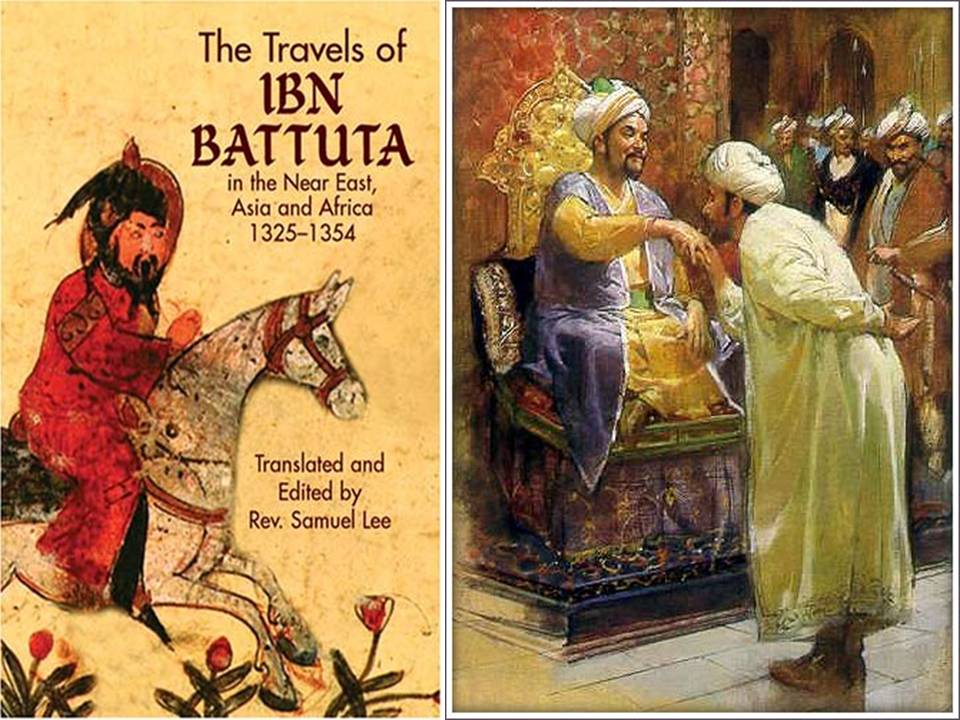

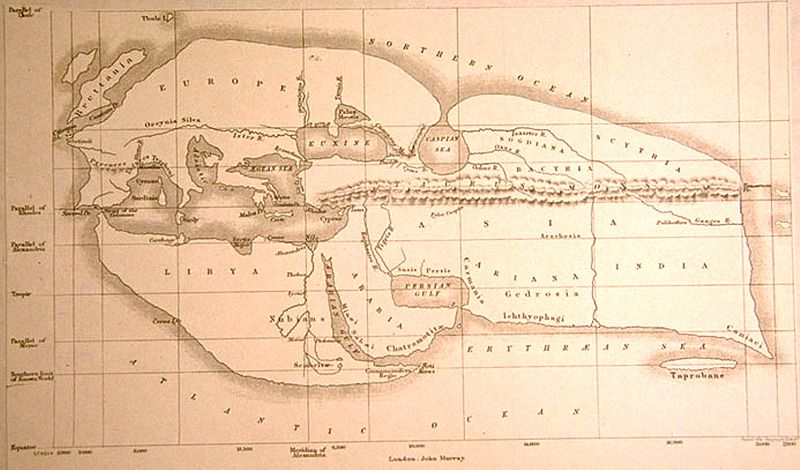

In 1325 Ibn Battuta had been a young man of 21, reluctantly leaving his parents to make his first hajj, or pilgrimage, to Mecca some 3,000 miles due east. He had covered those 3,000 miles and then had gone on to travel another 72,000 miles! Many Muslims made the pilgrimage to the Holy City but then returned home, for it was not an age when people were accustomed to straying from home for long periods. When Ibn Battuta began his travels, it was, in fact, more than 125 years before such renowned voyagers as Columbus, de Gama and Magellan set sail. It was no wonder, then, that Ibn Battuta returned to his native city, where his parents had died in his absence, to find himself a famous wayfarer. A contemporary described him as "the traveler of the age," adding' "he who should call him the traveler of the whole body of Islam would not exceed the truth."

Geographers and Explorers

Geographers and Explorers

He was the first person to use the word "geography" and invented the discipline of geography as we understand it.

He was the first person to use the word "geography" and invented the discipline of geography as we understand it.

First, though the book is commonly referred to as "the Rihla," that" is not its title, properly speaking, but its genre. (The title is Tuhfat al-Nuzzar fi Ghara'ib al-Amsar wa-'Aja'ib al-Asfar, or A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling.) The Prophet Muhammad's traditional injunction to "seek knowledge, even as far as China" had the effect of legitimating travel, or even wanderlust, and, in the Islamic middle ages, gave rise to the concept of al-rihla fi talab al-'ilm, travel in search of knowledge. In Islamic North Africa in the 12th to 14th centuries, as paper became increasingly widely available, educated men began to pen and circulate first-hand descriptions of their pilgrimages the Holy Cities of Makkah and Madinah. Such an account was called a rihla, or "travelogue," and it combined geographical and social information about the route with the writer's description of and emotional responses to the religious experience of the Hajj. The rihla is thus a category of Arab literature which Ibn Jubayr and, almost a century later, Ibn Battuta brought to its finest flowering.

First, though the book is commonly referred to as "the Rihla," that" is not its title, properly speaking, but its genre. (The title is Tuhfat al-Nuzzar fi Ghara'ib al-Amsar wa-'Aja'ib al-Asfar, or A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling.) The Prophet Muhammad's traditional injunction to "seek knowledge, even as far as China" had the effect of legitimating travel, or even wanderlust, and, in the Islamic middle ages, gave rise to the concept of al-rihla fi talab al-'ilm, travel in search of knowledge. In Islamic North Africa in the 12th to 14th centuries, as paper became increasingly widely available, educated men began to pen and circulate first-hand descriptions of their pilgrimages the Holy Cities of Makkah and Madinah. Such an account was called a rihla, or "travelogue," and it combined geographical and social information about the route with the writer's description of and emotional responses to the religious experience of the Hajj. The rihla is thus a category of Arab literature which Ibn Jubayr and, almost a century later, Ibn Battuta brought to its finest flowering.