The ecological footprint is a measure of human demand on the Earth's ecosystems. It is a standardized measure of demand for natural capital that may be contrasted with the planet's ecological capacity to regenerate.[1] It represents the amount of biologically productive land and sea area necessary to supply the resources a human population consumes, and to mitigate associated waste. Using this assessment, it is possible to estimate how much of the Earth (or how many planet Earths) it would take to support humanity if everybody followed a given lifestyle. For 2006, humanity's total ecological footprint was estimated at 1.4 planet Earths – in other words, humanity uses ecological services 1.4 times as fast as Earth can renew them.[2] Every year, this number is recalculated — with a three year lag due to the time it takes for the UN to collect and publish all the underlying statistics.

While the term ecological footprint is widely used,[3] methods of calculation vary. However, standards are now emerging to make results more comparable and consistent.[4]

Contents |

Analysis

Overview

The first academic publication about the ecological footprint was by William Rees in 1992.[5] The ecological footprint concept and calculation method was developed as the PhD dissertation of Mathis Wackernagel, under Rees' supervision at theUniversity of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, from 1990–1994.[6] Originally, Wackernagel and Rees called the concept "appropriated carrying capacity".[7] To make the idea more accessible, Rees came up with the term "ecological footprint," inspired by a computer technician who praised his new computer's "small footprint on the desk."[8] In early 1996, Wackernagel and Rees published the book Our Ecological Footprint: Reducing Human Impact on the Earth.[9]

Ecological footprint analysis compares human demand on nature with the biosphere's ability to regenerate resources and provide services. It does this by assessing the biologically productive land and marine area required to produce the resources a population consumes and absorb the corresponding waste, using prevailing technology. Footprint values at the end of a survey are categorized for Carbon, Food, Housing, and Goods and Services as well as the total footprint number of Earths needed to sustain the world's population at that level of consumption. This approach can also be applied to an activity such as the manufacturing of a product or driving of a car. This resource accounting is similar to life cycle analysis wherein the consumption of energy, biomass (food, fiber), building material, water and other resources are converted into a normalized measure of land area called 'global hectares' (gha).

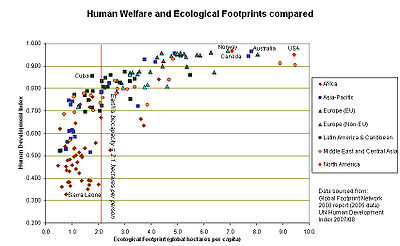

Per capita ecological footprint (EF) is a means of comparing consumption and lifestyles, and checking this against nature's ability to provide for this consumption. The tool can inform policy by examining to what extent a nation uses more (or less) than is available within its territory, or to what extent the nation's lifestyle would be replicable worldwide. The footprint can also be a useful tool to educate people about carrying capacity and over-consumption, with the aim of altering personal behavior. Ecological footprints may be used to argue that many current lifestyles are not sustainable. Such a global comparison also clearly shows the inequalities of resource use on this planet at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

In 2006, the average biologically productive area per person worldwide was approximately 1.8 global hectares (gha) per capita. The U.S. footprint per capita was 9.0 gha, and that of Switzerland was 5.6 gha per person, while China's was 1.8 gha per person.[10][11] The WWF claims that the human footprint has exceeded the biocapacity (the available supply of natural resources) of the planet by 20%.[12] Wackernagel and Rees originally estimated that the available biological capacity for the 6 billion people on Earth at that time was about 1.3 hectares per person, which is smaller than the 1.8 global hectares published for 2006, because the initial studies neither used global hectares nor included bioproductive marine areas.[9]

Ecological footprint analysis is now widely used around the globe as an indicator of environmental sustainability. It can be used to measure and manage the use of resources throughout the economy. It can be used to explore the sustainability of individual lifestyles, goods and services, organizations, industry sectors, neighborhoods, cities, regions and nations.[13] Since 2006, a first set of ecological footprint standards exist that detail both communication and calculation procedures. They are available at www.footprintstandards.org and were developed in a public process facilitated by Global Footprint Network and its partner organizations.

Ecology Writings

Ecology Writings

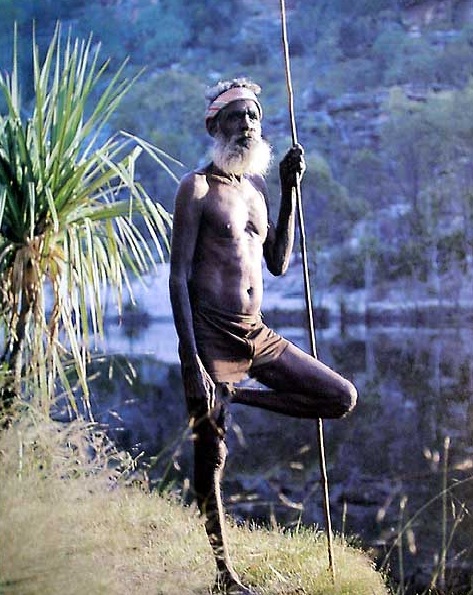

The Australian Aborigines' environmental culture and the "double bind" approach used in the program of Alcoholics Anonymous are considered as a source for the generation of a new strategy for dealing with the ecological problems of our day. The strategy aims at achieving a negotiated outcome in issues of high societal risk related to waste management in the Hawkesbury region of Sydney, Australia.

The Australian Aborigines' environmental culture and the "double bind" approach used in the program of Alcoholics Anonymous are considered as a source for the generation of a new strategy for dealing with the ecological problems of our day. The strategy aims at achieving a negotiated outcome in issues of high societal risk related to waste management in the Hawkesbury region of Sydney, Australia.