Ecological and Psychological Study

Deep Ecology is defined as:

- a philosophy based on our sacred relationship with Earth and all beings

- an international movement for a viable future

- a path for self realisation

- a compass for daily action

Deep Ecology Supports:

- continuing inquiry into the appropriate human roles on our planet

- root cause analysis of unsustainable practices

- reduction of human consumption

- conservation and restoration of ecosystems

- a life of committed action for Earth

Arne Naess’s original definition of ecosophy is:

"By an ecosophy I mean a philosophy of ecological harmony or equilibrium. A philosophy as a kind of sofia (or) wisdom, is openly normative, it contains both norms, rules, postulates, value priority announcements and hypotheses concerning the state of affairs in our universe. Wisdom is policy wisdom, prescription, not only scientific description and prediction. The details of an ecosophy will show many variations due to significant differences concerning not only the ‘facts’ of pollution, resources, population, etc. but also value priorities."

Read more...

Nature is the first ethical teacher of man.

-- Peter Kropotkin

Unless ye believe ye shall not understand. -- St Augustine

I was born a thousand years ago, born in the culture of bows and arrows ... born in an age when people loved the things of nature and spoke to it as though it had a soul. -- Chief Dan George

The woods were formerly temples of the deities, and even now simple country folk dedicate a tall tree to a God with the ritual of olden times; and we adore sacred groves and the very silence that reigns in them no less devoutly than images that gleam in gold and ivory. -- Pliny

In the stillness of the mighty woods, man is made aware of the divine. -- Richard St Barbe Baker

There is no better way to please the Buddha than to please all sentient beings. -- Ladakhi saying

Ecology and spirituality are fundamentally connected, because deep ecological awareness, ultimately, is spiritual awareness. -- Fritjof Capra

Every social transformation ... has rested on a new metaphysical and ideological base; or rather, upon deeper stirrings and intuitions whose rationalised expression takes the form of a new picture of the cosmos and the nature of man. -- Lewis Mumford

... there is reason to hope that the ecology-based revitalist movements of the future will seek to achieve their ends in the true Gandhian tradition. It could be that Deep Ecology, with its ethical and metaphysical preoccupations, might well develop into such a movement. -- Edward Goldsmith

The main hope for changing humanity's present course may lie ... in the development of a world view drawn partly from ecological principles - in the so-called deep ecology movement. -- Paul Ehrlich

The religious behaviour of man contributes to maintaining the sanctity of the world. -- Mircea Eliade

The Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess coined the phrase deep ecology to describe deep ecological awareness. Deep ecology is the foundation of a branch of philosophy known as ecophilosophy, Arne Naess prefers the term ecosophy, that deals with the ethics of Gaia.

Fritjof Capra defined deep ecology by contrasting it with shallow ecology and showing that it is a network concept:

Shallow ecology in anthropocentric, or human-centred. It views humans as above or outside of nature, as the source of all value, and ascribes only instrumental, or 'use', value to nature. Deep ecology does not separate humans - or anything else - from the natural environment. It does see the world not as a collection of isolated objects but as a network of phenomena that are fundamentally interconnected and interdependent. Deep ecology recognizes the intrinsic value of all living beings and views human beings as just one particular strand in the web of life.

Arne Naess formally defined deep ecology as Ecosophy T (N - norm, H - hypothesis).

- N1: Self-realization!

- H1: The higher the Self-realization attained by anyone, the broader and deeper the identification with others.

- H2: The higher the level of Self-realization attained by anyone, the more its further increase depends upon the Self-realization of others.

- H3: Complete Self-realization of anyone depends on that of all.

- N2: Self-realization for all living beings!

- H4: Diversity of life increases Self-realization potentials.

- N3: Diversity of life!

- H5: Complexity of life increases Self-realization potentials.

- N4: Complexity!

- H6: Life resources of the Earth are limited.

- H7: Symbiosis maximises Self-realization potentials under conditions of limited resources.

- N5: Symbiosis!

Arne Naess was strongly influenced by Baruch Spinoza and Mahatma Gandhi. Self-realisation is in the sense used by Gandhi.

Read more...

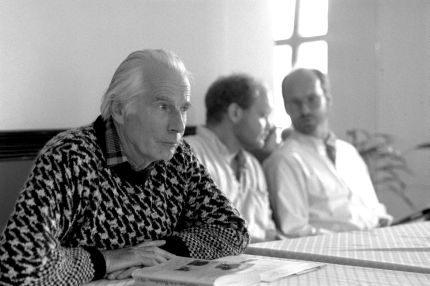

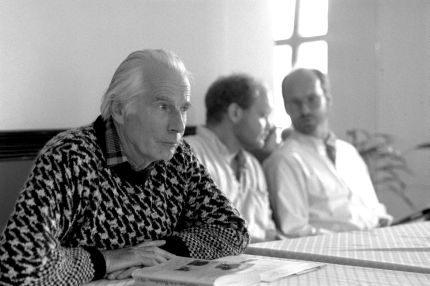

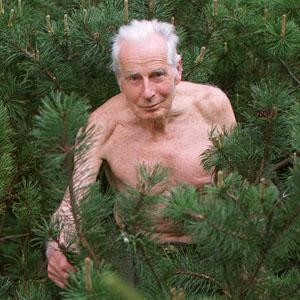

Arne Dekke Eide Næss (27 January 1912 – 12 January 2009) was the founder of deep ecology.[2] He was the youngest person to be appointed full professor at the University of Oslo. Arne Dekke Eide Næss (27 January 1912 – 12 January 2009) was the founder of deep ecology.[2] He was the youngest person to be appointed full professor at the University of Oslo.

Næss cited Rachel Carson's 1962 book Silent Spring as being a key influence in his vision of deep ecology. Næss combined his ecological vision with Gandhian nonviolence and on several occasions participated in direct action. In 1970, together with a large number of demonstrators, he chained himself to rocks in front of Mardalsfossen, a waterfall in a Norwegian fjord, and refused to descend until plans to build a dam were dropped. Though the demonstrators were carried away by police and the dam was eventually built, the demonstration launched a more activist phase of Norwegian environmentalism[3]. In 1958, Arne Næss founded the interdiciplinary journal of philosophy Inquiry.

Næss had been a minor political candidate for the Norwegian Green Party.[4]

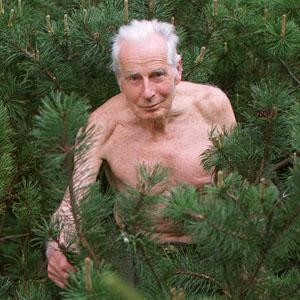

Næss was a noted mountaineer, who in 1950 led the expedition that made the first ascent of Tirich Mir (7,708 m). The Tvergastein hut in the Hallingskarvet massif played an important role in Næss' life.

Philosophy

Arne Næss' main philosophical work from the 1950s was entitled "Interpretation and Preciseness". This was an application of set theory to the problems of language interpretation, extending the work of such logicians as Leonhard Euler, and semanticists such as Charles Kay Ogden in The Meaning of Meaning. A simple way of explaining it is that any given utterance (word, phrase, or sentence) can be considered as having different potential interpretations, depending on prevailing language norms, the characteristics of particular persons or groups of users, and the language situation in which the utterance occurred. These differing interpretations are to be formulated in more precise language represented as subsets of the original utterance. Each subset can, in its turn, have further subsets (theoretically ad infinitum). The advantages of this conceptualisation of interpretation are various. It enables systematic demonstration of possible interpretation, making possible evaluation of which are the more and less "reasonable interpretations". It is a logical instrument for demonstrating language vagueness, undue generalisation, conflation, pseudo-agreement and effective communication.

Næss developed a simplified, practical textbook embodying these advantages, entitled Communication and Argument, which became a valued introduction to this pragmatics or "language logic", and was used over many decades as a sine qua non for the preparatory examination at the University of Oslo, later known as "Examen Philosophicum" ("Exphil").

Read more...

Those who love wild nature and work toward a day when humankind might inhabit this abundant planet with greater wonder, humility, and compassion, mourn the loss of a great ecological visionary - Arne Naess - who died on January 12, leaving behind a legacy of environmental awareness and action.

Naess, one of the most influential philosophers of his generation, died in his sleep at the age of 96 in Oslo, Norway. The avid mountaineer founded the Deep Ecology movement, drawing inspiration from Buddhism, Rachel Carson, Aldo Leopold, and above all from nature itself. Greenpeace can be proud that he served as the first chairman of Greenpeace Norway in 1988. His personal story illuminates the path of ecology in the 21st century.

Arne Naess at the opening of the Greenpeace office in Oslo, 1988

(c) Henrik Laurvik NTB/Scanpix - used under licence

On the mountain

Naess was born in 1912, in Slemdal, near Oslo, and his father, banker Ragnar Naess, died the next year. Naess later recalled that his mother, Christine Dekke, appeared preoccupied with raising his two older brothers, so he often wandered alone into nature for companionship.

In How My Philosophy Seemed to Develop he revealed, at the age of four, "I would stand or sit for hours … in shallow water on the coast, marvelling at the overwhelming diversity and richness of life in the sea."

At the age of 17, while climbing on Norway's Hallingskarvet massif, he met a kind Norwegian judge, who also adored nature. This mentor advised young Arne to read Dutch Jewish philosopher Spinoza, who equated the 'highest virtue' with knowledge of nature. For Spinoza, Naess learned, all thinking about truth and human society begins with recognising the basic 'substance', the diversity and magnificence of the natural world.

In his 20s, Naess built a life-long writing cabin, Tvergastein, high on this mountain. "In the mountains," Naess once said, "you are small compared to the surrounding view, so you more easily and more intensely feel that you are a part of something greater. You find that your idea of your 'self' is more vast and deeper." This depth he felt in vast nature - mountains, sea, forests - inspired his use of the word 'deep' to describe his understanding of ecology

Read more...

Social Ecology versus Deep Ecology: A Challenge for the Ecology Movement

by Murray Bookchin

[Originally published in Green Perspectives: Newsletter of the Green Program Project, nos. 4-5 (summer 1987). In the original, the term deep ecology appeared in quotation marks; they have been removed in this online posting.]

The environmental movement has traveled a long way since those early Earth Day festivals when millions of school kids were ritualistically mobilized to clean up streets, while Arthur Godfrey, Barry Commoner, Paul Ehrlich, and a bouquet of manipulative legislators scolded their parents for littering the landscape with cans, newspapers, and bottles.

The movement has gone beyond a naive belief that patchwork reforms and solemn vows by EPA bureaucrats to act more resolutely will seriously arrest the insane pace at which we are tearing down the planet. This shopworn Earth Day approach to engineering nature so that we can ravage the Earth with minimal effect on ourselves---an approach that I called environmentalism in the late 1960s, in contrast to social ecology---has shown signs of giving way to a more searching and radical mentality. Today the new word in vogue is ecology---be it deep ecology, human ecology, biocentric ecology, antihumanist ecology, or to use a term that is uniquely rich in meaning, social ecology.

Read more...

Deep ecology is a somewhat recent branch of ecological philosophy (ecosophy) that considers humankind as an integral part of its environment. The philosophy emphasizes the interdependent value of human and non-human life as well as the importance of the ecosystem and natural processes. It provides a foundation for the environmental and green movements and has led to a new system of environmental ethics. Deep ecology is a somewhat recent branch of ecological philosophy (ecosophy) that considers humankind as an integral part of its environment. The philosophy emphasizes the interdependent value of human and non-human life as well as the importance of the ecosystem and natural processes. It provides a foundation for the environmental and green movements and has led to a new system of environmental ethics.

Deep ecology's core principle is the claim that, like humanity, the living environment as a whole has the same right to live and flourish. Deep ecology describes itself as "deep" because it persists in asking deeper questions concerning "why" and "how" and thus is concerned with the fundamental philosophical questions about the impacts of human life as one part of the ecosphere, rather than with a narrow view of ecology as a branch of biological science, and aims to avoid merely anthropocentric environmentalism, which is concerned with conservation of the environment only for exploitation by and for humans purposes, which excludes the fundamental philosophy of deep ecology. Deep ecology seeks a more holistic view of the world we live in and seeks to apply to life the understanding that separate parts of the ecosystem (including humans) function as a whole.

Development

The phrase "deep ecology" was coined by the Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess in 1973,[1] and he helped give it a theoretical foundation. "For Arne Naess, ecological science, concerned with facts and logic alone, cannot answer ethical questions about how we should live. For this we need ecological wisdom. Deep ecology seeks to develop this by focusing on deep experience, deep questioning and deep commitment. These constitute an interconnected system. Each gives rise to and supports the other, whilst the entire system is, what Næss would call, an ecosophy: an evolving but consistent philosophy of being, thinking and acting in the world, that embodies ecological wisdom and harmony."[2] Næss rejected the idea that beings can be ranked according to their relative value. For example, judgments on whether an animal has an eternal soul, whether it uses reason or whether it has consciousness (or indeed higher consciousness) have all been used to justify the ranking of the human animal as superior to other animals. Næss states that from an ecological point of view "the right of all forms [of life] to live is a universal right which cannot be quantified. No single species of living being has more of this particular right to live and unfold than any other species." This metaphysical idea is elucidated in Warwick Fox's claim that we and all other beings are "aspects of a single unfolding reality".[3]. As such Deep Ecology would support the view of Aldo Leopold in his book, A Sand County Almanac that humans are "plain members of the biotic community". They also would support Leopold's "Land Ethic": "a thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise." Daniel Quinn in Ishmael, showed that an anthropocentric myth underlies our current view of the world, and a jellyfish would have an equivalent jellyfish centric view[4]. The phrase "deep ecology" was coined by the Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess in 1973,[1] and he helped give it a theoretical foundation. "For Arne Naess, ecological science, concerned with facts and logic alone, cannot answer ethical questions about how we should live. For this we need ecological wisdom. Deep ecology seeks to develop this by focusing on deep experience, deep questioning and deep commitment. These constitute an interconnected system. Each gives rise to and supports the other, whilst the entire system is, what Næss would call, an ecosophy: an evolving but consistent philosophy of being, thinking and acting in the world, that embodies ecological wisdom and harmony."[2] Næss rejected the idea that beings can be ranked according to their relative value. For example, judgments on whether an animal has an eternal soul, whether it uses reason or whether it has consciousness (or indeed higher consciousness) have all been used to justify the ranking of the human animal as superior to other animals. Næss states that from an ecological point of view "the right of all forms [of life] to live is a universal right which cannot be quantified. No single species of living being has more of this particular right to live and unfold than any other species." This metaphysical idea is elucidated in Warwick Fox's claim that we and all other beings are "aspects of a single unfolding reality".[3]. As such Deep Ecology would support the view of Aldo Leopold in his book, A Sand County Almanac that humans are "plain members of the biotic community". They also would support Leopold's "Land Ethic": "a thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise." Daniel Quinn in Ishmael, showed that an anthropocentric myth underlies our current view of the world, and a jellyfish would have an equivalent jellyfish centric view[4].

Read more...

|

|

Deep Ecology

Deep Ecology

The phrase "deep ecology" was coined by the Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess in 1973,[1] and he helped give it a theoretical foundation. "For Arne Naess, ecological science, concerned with facts and logic alone, cannot answer ethical questions about how we should live. For this we need ecological wisdom. Deep ecology seeks to develop this by focusing on deep experience, deep questioning and deep commitment. These constitute an interconnected system. Each gives rise to and supports the other, whilst the entire system is, what Næss would call, an ecosophy: an evolving but consistent philosophy of being, thinking and acting in the world, that embodies ecological wisdom and harmony."[2] Næss rejected the idea that beings can be ranked according to their relative value. For example, judgments on whether an animal has an eternal soul, whether it uses reason or whether it has consciousness (or indeed higher consciousness) have all been used to justify the ranking of the human animal as superior to other animals. Næss states that from an ecological point of view "the right of all forms [of life] to live is a universal right which cannot be quantified. No single species of living being has more of this particular right to live and unfold than any other species." This metaphysical idea is elucidated in Warwick Fox's claim that we and all other beings are "aspects of a single unfolding reality".[3]. As such Deep Ecology would support the view of Aldo Leopold in his book, A Sand County Almanac that humans are "plain members of the biotic community". They also would support Leopold's "Land Ethic": "a thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise." Daniel Quinn in Ishmael, showed that an anthropocentric myth underlies our current view of the world, and a jellyfish would have an equivalent jellyfish centric view[4].

The phrase "deep ecology" was coined by the Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess in 1973,[1] and he helped give it a theoretical foundation. "For Arne Naess, ecological science, concerned with facts and logic alone, cannot answer ethical questions about how we should live. For this we need ecological wisdom. Deep ecology seeks to develop this by focusing on deep experience, deep questioning and deep commitment. These constitute an interconnected system. Each gives rise to and supports the other, whilst the entire system is, what Næss would call, an ecosophy: an evolving but consistent philosophy of being, thinking and acting in the world, that embodies ecological wisdom and harmony."[2] Næss rejected the idea that beings can be ranked according to their relative value. For example, judgments on whether an animal has an eternal soul, whether it uses reason or whether it has consciousness (or indeed higher consciousness) have all been used to justify the ranking of the human animal as superior to other animals. Næss states that from an ecological point of view "the right of all forms [of life] to live is a universal right which cannot be quantified. No single species of living being has more of this particular right to live and unfold than any other species." This metaphysical idea is elucidated in Warwick Fox's claim that we and all other beings are "aspects of a single unfolding reality".[3]. As such Deep Ecology would support the view of Aldo Leopold in his book, A Sand County Almanac that humans are "plain members of the biotic community". They also would support Leopold's "Land Ethic": "a thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise." Daniel Quinn in Ishmael, showed that an anthropocentric myth underlies our current view of the world, and a jellyfish would have an equivalent jellyfish centric view[4].