Kew Gardens

| Kew Gardens | |

|---|---|

A view across the gardens to the Palm House in Kew Gardens, in London, England | |

| |

| Type | Botanical |

| Location | London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England |

| Coordinates | 51°28′44″N 00°17′37″W / 51.47889°N 0.29361°W |

| Area | 121 hectares (300 acres) |

| Opened | 1759 |

| Visitors | more than 1.35 million per year |

| Species | > 50,000 |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii), (iii), (iv) |

| Reference | 1084 |

| Inscription | 2003 (27th Session) |

| Area | 132 ha (330 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 350 ha (860 acres) |

Kew Gardens is a botanic garden in southwest London that houses the "largest and most diverse botanical and mycological collections in the world".[1] Founded in 1840, from the exotic garden at Kew Park, its living collections include some of the 27,000 taxa[2] curated by Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, while the herbarium, one of the largest in the world, has over 8.5 million preserved plant and fungal specimens.[3] The library contains more than 750,000 volumes, and the illustrations collection contains more than 175,000 prints and drawings of plants. It is one of London's top tourist attractions and is a World Heritage Site.[4][5]

Kew Gardens, together with the botanic gardens at Wakehurst in Sussex, are managed by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, an internationally important botanical research and education institution that employs over 1,100 staff and is a non-departmental public body sponsored by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.[6]

The Kew site, which has been dated as formally starting in 1759,[7] although it can be traced back to the exotic garden at Kew Park, formed by Henry, Lord Capell of Tewkesbury, consists of 132 hectares (330 acres)[8] of gardens and botanical glasshouses, four Grade I listed buildings, and 36 Grade II listed structures, all set in an internationally significant landscape.[9] It is listed Grade I on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[10]

Kew Gardens has its own police force, Kew Constabulary, which has been in operation since 1845.[11]

History[edit]

Kew consists mostly of the gardens themselves and a small surrounding community.[12] Royal residences in the area which would later influence the layout and construction of the gardens began in 1299 when Edward I moved his court to a manor house in neighbouring Richmond (then called Sheen).[12] That manor house was later abandoned; however, Henry VII built Sheen Palace in 1501, which, under the name Richmond Palace, became a permanent royal residence for Henry VII.[13][14][15] Around the start of the 16th century courtiers attending Richmond Palace settled in Kew and built large houses.[12] Early royal residences at Kew included Mary Tudor's house, which was in existence by 1522 when a driveway was built to connect it to the palace at Richmond.[12] Around 1600, the land that would become the gardens was known as Kew Field, a large field strip farmed by one of the new private estates.[16][17]

The exotic garden at Kew Park, formed by Henry Capell, 1st Baron Capell of Tewkesbury, was enlarged and extended by Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales, the widow of Frederick, Prince of Wales. The origins of Kew Gardens can be traced to the merging of the royal estates of Richmond and Kew in 1772.[18] William Chambers built several garden structures, including the lofty Great Pagoda built in 1761 which still remains. George III enriched the gardens, aided by William Aiton and Sir Joseph Banks.[19] The old Kew Park (by then renamed the White House), was demolished in 1802. The "Dutch House" adjoining was purchased by George III in 1781 as a nursery for the royal children. It is a plain brick structure now known as Kew Palace.

The Epicure's Almanack reports an anecdote of the garden wall as of 1815: "In going up Dreary Lane that leads to Richmond you pass along the east boundary wall of Kew Gardens, extending more than a mile in length. This dead wall used to have a most teasing and tedious effect on the eye of a pedestrian; but a poor mendicant crippled seaman, some years ago, enlivened it by drawing on it, in chalk, every man of war in the British navy. He returns annually to the spot to refit his ships, and raises considerable supplies for his own victualling board from the gratuities of the charitable, who pass to and from Richmond."[20]

Some early plants came from the walled garden established by William Coys at Stubbers in North Ockendon.[21] The collections grew somewhat haphazardly until the appointment of the first collector, Francis Masson, in 1771.[22] Capability Brown, who became England's most renowned landscape architect, applied for the position of master gardener at Kew, and was rejected.[23]

In 1840, the gardens were adopted as a national botanical garden, in large part due to the efforts of the Royal Horticultural Society and its president William Cavendish.[24] Under Kew's director, William Hooker, the gardens were increased to 30 hectares (75 acres) and the pleasure grounds, or arboretum, extended to 109 hectares (270 acres), and later to its present size of 121 hectares (300 acres). The first curator was John Smith.

The Palm House was built by architect Decimus Burton and iron-maker Richard Turner between 1844 and 1848, and was the first large-scale structural use of wrought iron. It is considered "the world's most important surviving Victorian glass and iron structure".[25][26] The structure's panes of glass are all hand-blown. The Temperate House, which is twice as large as the Palm House, followed later in the 19th century. It is now the largest Victorian glasshouse in existence. Kew was the location of the successful effort in the 19th century to propagate rubber trees for cultivation outside South America.

In February 1913, the Tea House was burned down by suffragettes Olive Wharry and Lilian Lenton during a series of arson attacks in London.[27]

Kew Gardens lost hundreds of trees in the Great Storm of 1987.[28]

From 1959 to 2007, Kew Gardens had the tallest flagpole in Britain. Made from a single Douglas-fir from Canada, it was given to mark both the centenary of the Canadian province of British Columbia and the bicentenary of Kew Gardens. The flagpole was removed after damage by weather and woodpeckers made it a danger.[29]

In July 2003, UNESCO put the gardens on its list of World Heritage Sites.[7]

A five-year, £41 million revamp of the Temperate House was completed in May 2018.[30]

Five trees survive from the establishment of the botanical gardens in 1762. Together they are known as the 'Five Lions' and consist of: a ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba), a pagoda tree, or scholar tree (Styphnolobium japonicum), an oriental plane (Platanus orientalis),[31] a black locust, or false acacia (Robinia pseudoacacia), and a Caucasian elm or zelkova (Zelkova carpinifolia).[32]

Features[edit]

Treetop walkway[edit]

A canopy walkway, which opened in 2008,[33] takes visitors on a 200 metres (660 ft) walk 18 metres (59 ft) above the ground, in the tree canopy of a woodland glade. Visitors can ascend and descend by stairs and by a lift. The walkway floor is perforated metal and flexes under foot; the entire structure sways in the wind. It was designed by David Marks.[34]

The accompanying photograph shows a section of the walkway, including the steel supports, which were designed to rust to a tree-like appearance to help the walkway fit in visually with its surroundings.[35]

A short video detailing the construction of the walkway is available online.[36]

Lake Crossing[edit]

The Lake Crossing bridge, made of granite and bronze, opened in May 2006.[37] Designed by Buro Happold and John Pawson, it crosses the lake and was previously named in honor of Dr Mortimer and Theresa Sackler.[38]

The minimalist-styled bridge is designed as a sweeping double curve of black granite. The sides of the bridge are formed of bronze posts that give the impression, from certain angles, of forming a solid wall while, from others, and to those on the bridge, they are clearly individual entities that allow a view of the water beyond.[37]

The bridge forms part of a path designed to encourage visitors to visit more of the gardens than had hitherto been popular and connects the two art galleries, via the Temperate and Evolution Houses and the woodland glade, to the Minka House and the Bamboo Garden.[39]

The crossing won a special award from the Royal Institute of British Architects in 2008.[40]

The Hive[edit]

The Hive opened in 2016 and is a multi-sensory experience designed to highlight the extraordinary life of bees. It stands 17 metres (56 ft) tall and is set in a wildflower meadow. The Hive was designed by English artist Wolfgang Buttress. The Hive has been created using thousands of aluminium pieces that are presented in the shape of a honeycomb. It was initially installed as a temporary exhibition, but was given a permanent home at Kew Gardens due to its popularity.[41]

Vehicular tour[edit]

Kew Explorer is a service that takes a circular route around the gardens, provided by two 72-seater road trains that are fuelled by Calor Gas to minimize pollution. A commentary is provided by the driver and there are several stops.[42]

A map of the gardens is available on the Kew Gardens website.[39]

Compost heap[edit]

Kew has one of the largest compost heaps in Europe, made from green and woody waste from the gardens and the manure from the stables of the Household Cavalry.[43] The compost is mainly used in the gardens, but on occasion has been auctioned as part of a fundraising event for the gardens.[44]

The compost heap is in an area of the gardens not accessible to the public,[43] but a viewing platform, made of wood which had been illegally traded but seized by Customs officers in HMRC, has been erected to allow visitors to observe the heap as it goes through its cycle.[44]

Guided walks[edit]

Tours of the gardens are conducted daily by trained volunteers.[45]

Plant houses[edit]

Alpine House[edit]

In March 2006, the Davies Alpine House opened, the third version of an alpine house since 1887. Although only 16 metres (52 ft) long the apex of the roof arch extends to a height of 10 metres (33 ft) in order to allow the natural airflow of a building of this shape to aid in the all-important ventilation required for the type of plants to be housed.

The new house features a set of automatically operated blinds that prevent it from overheating when the sun is too hot for the plants together with a system that blows a continuous stream of cool air over the plants. The main design aim of the house is to allow maximum light transmission. To this end the glass is of a special low iron type that allows 90 per cent of the ultraviolet light in sunlight to pass. It is attached by high tension steel cables so that no light is obstructed by traditional glazing bars.

To conserve energy the cooling air is not refrigerated but is cooled by being passed through a labyrinth of pipes buried under the house at a depth where the temperature remains suitable all year round. The house is designed so that the maximum temperature should not exceed 20 °C (68 °F).

Kew's collection of alpine plants (defined as those that grow above the tree line in their locale – ground level at the poles rising to over 2,000 metres (6,562 feet)), extends to over 7000. As the Alpine House can only house around 200 at a time the ones on show are regularly rotated.

Nash Conservatory[edit]

Originally designed for Buckingham Palace, this was moved to Kew in 1836 by King William IV. The building was formerly known as the Aroid House No. 1 and was used to display species of Araceae, the building was listed Grade II* in 1950.[46] With an abundance of natural light, the building is now used for various exhibitions, weddings, and private events. It is also now used to exhibit the winners of the photography competition.

Orangery[edit]

The Orangery[47] was designed by Sir William Chambers, and was completed in 1761. It measures 28 by 10 metres (92 by 33 ft). It was found to be too dark for its intended purpose of growing citrus plants and they were moved out in 1841. After many changes of use, it is currently used as a restaurant.

Palm House[edit]

The Palm House (1844–1848) was the result of cooperation between architect Decimus Burton and iron founder Richard Turner,[48] and continues upon the glass house design principles developed by John Claudius Loudon[49][50] and Joseph Paxton.[50] A space frame of wrought iron arches, held together by horizontal tubular structures containing long prestressed cables,[50][51] supports glass panes which were originally[48] tinted green with copper oxide to reduce the significant heating effect. The 19 metres (62 ft) high central nave is surrounded by a walkway at 9 metres (30 ft) height, allowing visitors a closer look upon the palm tree crowns. In front of the Palm House on the east side are the Queen's Beasts, ten statues of animals bearing shields. They are Portland stone replicas of originals done by James Woodford and were placed here in 1958.[52]

The Palm House was originally heated by two coal-fired boilers, with a 107 feet (33 m) chimney, the "Shaft of the Great Palm-Stove", now known as the Campanile, near the Victoria Gate. Coal was brought in by a light railway, running in a tunnel, using human-propelled wagons. The tunnel acted as a flue between the boilers and the chimney, but the distance proved too great for efficient working, and so two small chimneys were added to the Palm House. In 1950 the railway was electrified. The tunnel is now used to carry piped hot water to the Palm House, from oil-fired boilers located near the original chimney, which is extant, and is Grade II listed.[53]

Princess of Wales Conservatory[edit]

Kew's third major conservatory, the Princess of Wales Conservatory, designed by architect Gordon Wilson, was opened in 1987 by Diana, Princess of Wales in commemoration of her predecessor Augusta's associations with Kew.[54] It replaced 26 smaller buildings.[55] In 1989 the conservatory received the Europa Nostra award for conservation.[56] The conservatory houses ten computer-controlled micro-climatic zones, with the bulk of the greenhouse volume composed of Dry Tropics and Wet Tropics plants. Significant numbers of orchids, water lilies, cacti, lithops, carnivorous plants and bromeliads are housed in the various zones. The cactus collection also extends outside the conservatory where some hardier species can be found.

The conservatory has an area of 4,499 square metres (48,430 sq ft; 0.4499 ha; 1.112 acres). As it is designed to minimize the amount of energy taken to run it, the cooler zones are grouped around the outside and the more tropical zones are in the central area where heat is conserved. The glass roof extends down to the ground, giving the conservatory a distinctive appearance and helping to maximize the use of the sun's energy.

During the construction of the conservatory a time capsule was buried. It contains the seeds of basic crops and endangered plant species and key publications on conservation.[56]

The Temperate House[edit]

The Temperate House, re-opened in May 2018 after being closed for restoration, is a greenhouse that has twice the floor area of the Palm House and is the world's largest surviving Victorian glass structure. It contains plants and trees from all the temperate regions of the world, some of which are extremely rare. It was commissioned in 1859 and designed by architect Decimus Burton and iron founder Richard Turner. Covering 4880 square metres, it rises to a height of 19 metres (62 ft). Intended to accommodate Kew's expanding collection of hardy and temperate plants, it took 40 years to construct, during which time costs soared. The building was closed for restoration 1980–82. The building was restored during 2014–15 by Donald Insall Associates, based on their conservation management plan.[57]

There is a viewing gallery in the central section from which visitors can look down on that part of the collection.

Waterlily House[edit]

The Waterlily House is the hottest and most humid of the houses at Kew and contains a large pond with varieties of water lily, surrounded by a display of economically important heat-loving plants. It closes during the winter months.

It was built to house Victoria amazonica, the largest of the water lily family Nymphaeaceae. This plant was originally transported to Kew in vials of clean water and arrived in February 1849, after several prior attempts to transport seeds and roots had failed. Although various other members of Nymphaeaceae grew well, the house did not suit the Victoria, purportedly because of a poor ventilation system, and this specimen was moved to another, smaller, house (Victoria amazonica House No. 10).

The ironwork for the Waterlily House project was provided by Richard Turner and the initial construction was completed in 1852. The heat for the house was initially obtained by running a flue from the nearby Palm House but it was later equipped with its own boiler.[58]

Evolution House[edit]

Formerly known as the Australian House. The house was a gift from the Australian Government. It was designed by S L Rothwell (Ministry of Works) with consultant engineer J E Temple and was constructed by the Crittall Manufacturing Company Ltd. It opened in 1952. From 1995 it was known as the Evolution House. The building is listed under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 for its special architectural or historic interest.[59]

Bonsai House[edit]

The Bonsai House was formerly known as the Alpine House No. 24 prior to the construction of the Davies Alpine House.

Former plant houses[edit]

The following plant houses were in use in 1974. All have since been demolished.[60]

| Official number | Name | Notes |

| No. 2 | Tropical Fern House | Located in the gardens to the north of the Princess of Wales Conservatory |

| No. 3 | Temperate Fern House | |

| No. 4 | Conservatory | |

| No. 5 | Succulent House | |

| No. 7 | Gesneriads and Rhipsalis | Located on the site of the Princess of Wales Conservatory. Plant Houses Nos. 7 to 14b inclusive were collectively known as the "T" Range because of their T-shaped plan. |

| No. 7a | Sherman Hoyt House | |

| No. 7b | South African Succulent House | |

| No. 8 | Orchid House | |

| No. 9 | Orchid House | |

| No. 9a | Nepenthes | |

| No. 10 | Victoria amazonica House | |

| No. 10a | Impatiens | |

| No. 11 | Bromeliad House | |

| No. 12 | South African House | |

| No. 12a | Insectivorous Plants House | |

| No. 14a | Begonia House | |

| No. 14b | Begonia House | |

| – | Filmy Fern House | Located on the north face of Orangery |

The extant Aroid House (now the Nash Conservatory) was designated Plant House No. 1 and the Water Lily House was Plant House No. 15.

Ornamental buildings[edit]

Great Pagoda[edit]

In the southeast corner of Kew Gardens stands the Great Pagoda (by Sir William Chambers), erected in 1762, from a design in imitation of the Chinese Ta. The lowest of the ten octagonal storeys is 15 m (49 ft) in diameter. From the base to the highest point is 50 m (164 ft).

Each storey finishes with a projecting roof, after the Chinese manner, originally covered with ceramic tiles and adorned with large dragons; a tale is still propagated that they were made of gold and were reputedly sold by George IV to settle his debts.[61] In fact the dragons were made of wood painted gold, and simply rotted away with the ravages of time. The walls of the building are composed of brick. The staircase, 253 steps, is in the center of the building. During the Second World War holes were cut in each floor to allow for drop-testing of model bombs.

The Pagoda was closed to the public for many years but was reopened for the summer months of 2006. It has been renovated in a major restoration project and reopened under the aegis of Historic Royal Palaces in 2018.[62] 80 dragons have been remade and now sit on each storey of the building.

Japanese Gateway (Chokushi-Mon)[edit]

Built for the Japan-British Exhibition (1910) and moved to Kew in 1911, the Chokushi-Mon ("Imperial Envoy's Gateway") is a four-fifths scale replica of the karamon (gateway) of the Nishi Hongan-ji temple in Kyoto. It lies about 140 m north of the Pagoda and is surrounded by a reconstruction of a traditional Japanese garden.

Minka House[edit]

Following the Japan 2001 festival,[63] Kew acquired a Japanese wooden house called a minka. It was originally erected in around 1900 in a suburb of Okazaki and is now located within the bamboo collection in the west-central part of Kew Gardens. Japanese craftsmen reassembled the framework and British builders who had worked on the Globe Theatre added the mud wall panels.

Work on the house started on 7 May 2001 and, when the framework was completed on 21 May, a Japanese ceremony was held to mark what was considered an auspicious occasion. Work on the building of the house was completed in November 2001 but the internal artifacts were not all in place until 2006.

Queen Charlotte's Cottage[edit]

Within the conservation area is a cottage that was built sometime before 1771 for Queen Charlotte by her husband George III. It has been restored by Historic Royal Palaces and is separately administered by them.[64] It is open to the public on weekends and bank holidays during the summer.

King William's Temple[edit]

A double porticoed Doric temple in stone with a series of cast-iron panels set in the inside walls commemorating British military victories from Minden (1759) to Waterloo (1815). It was built in 1837 by Sir Jeffery Wyatville, and originally called The Pantheon. Named after King William IV (1830–37). It is Grade II listed.[65]

Temple of Aeolus[edit]

A domed rotunda with eight Tuscan columns. The original temple was built in 1763 by Sir William Chambers. The present temple is an 1845 replacement by Decimus Burton. It is Grade II listed.[66] The temple was one of three originally named to honour British victories in the Seven Years' War, in this case the name commemorates HMS Aeolus.[67]

Temple of Arethusa[edit]

A small Greek temple portico with two Ionic columns and two outer Ionic pillars; it is pedimented with a cornice and key pattern frieze. It was built in 1758 by Sir William Chambers. It is Grade II listed.[68] Similar to the temple of Aeolus and Bellona, she was later named to commemorate the warship HMS Arethusa.[67]

Temple of Bellona[edit]

A whitewashed stucco temple. The facade has a portico of two pairs of Doric columns with a metope frieze pediment and an oval dome behind. Inside is a room with an oval domed center. On the walls garlands and medallions with the names and numbers of British and Hanovarian units connected with the Seven Years' War. It was built in 1760 by Sir William Chambers and eventually named after HMS Bellona.[67] It is Grade II listed.[69]

The Ruined Arch[edit]

A brick arch with rustication in stucco. A triple-arched opening with oculi above lower side arches, it has a stone band course and a fragmented blocked cornice and brick offering, and a corniced doorway. It was built in 1759–60 by Sir William Chambers. It is Grade II* listed.[70]

Ice House[edit]

The Ice House is believed to be early 18th-century, it has a brick dome with an access arch and barrel-vaulted passageway, covered by a mound of earth. It is Grade II listed.[71]

Kew Palace[edit]

Kew Palace is the smallest of the British royal palaces. It was built by Samuel Fortrey, a Dutch merchant in around 1631. It was later purchased by George III. The construction method is known as Flemish bond and involves laying the bricks with long and short sides alternating. This and the gabled front give the construction a Dutch appearance.

To the rear of the building is the "Queen's Garden" which includes a collection of plants believed to have medicinal qualities. Only plants that were extant in England by the 17th century are grown in the garden.

The building underwent significant restoration, with leading conservation architects Donald Insall Associates, before being reopened to the public in 2006.[72] It is administered separately from Kew Gardens, by Historic Royal Palaces.

In front of the palace is a sundial, which was given to Kew Gardens in 1959 to commemorate a royal visit. It was sculpted by Martin Holden and is a replica of one by Thomas Tompion, a celebrated 17th-century clockmaker, which had been sited near the surviving palace building since 1832 to mark the site of James Bradley's observations leading to his discovery of the aberration of light.[73][74]

Galleries and museums[edit]

Admission to the galleries and museum is free after paying admission to the gardens. The International Garden Photographer of the Year Exhibition is an annual event with an indoor display of entries during the summer months.

Shirley Sherwood Gallery[edit]

The Shirley Sherwood Gallery of Botanic Art opened in April 2008, and holds paintings from Kew's and Dr Shirley Sherwood's collections, many of which had never been displayed to the public before. It features paintings by artists such as Georg D. Ehret, the Bauer brothers, Pierre-Joseph Redouté and Walter Hood Fitch. The paintings and drawings are cycled on a six-monthly basis. The gallery is linked to the Marianne North Gallery (see below).

Museum No. 1[edit]

Near the Palm House is a building known as the General Museum or "Museum No. 1" (even though it is now the only museum on the site), which was designed by Decimus Burton and opened in 1857. Housing Kew's economic botany collections including tools, ornaments, clothing, food and medicines, its aim was to illustrate human dependence on plants. The building was refurbished in 1998. The upper two floors are now an education center and the ground floor houses The Botanical restaurant. Due to its historical holdings, Kew is a member of The London Museums of Health & Medicine group.[75]

Marianne North Gallery[edit]

The Marianne North Gallery was built in the 1880s to house the paintings of Marianne North, an MP's daughter who travelled alone to North and South America, South Africa, and many parts of Asia, at a time when women rarely did so, to paint plants. The gallery has 832 of her paintings. She left the paintings to Kew on condition that the layout of the paintings in the gallery would not be altered.

The gallery had suffered considerable structural degradation since its creation and during a period from 2008 to 2009 major restoration and refurbishment took place, with works led by leading conservation architects Donald Insall Associates.[76] During the time the gallery was closed the opportunity was also taken to restore the paintings to their original condition. The gallery reopened in October 2009.

The gallery originally opened in 1882 and is still the only permanent exhibition in Great Britain dedicated to the work of one woman.

Former museum buildings[edit]

The School of Horticulture building was formerly known as the Reference Museum or Museum No. 2.[60]

Museum No. 3 was originally known as the Timber Museum, it opened in 1863 and closed in 1958.[77]

Cambridge Cottage is a former residence of the Duke of Cambridge (1819–1904).[78] It became part of the gardens in 1904, and was opened in 1910 as the Museum of British Forestry or Museum No. 4.[77] After 1958 it was known as the Wood Museum and displayed samples of wood from around the world.[60] It is Grade II listed.[79] Today it is a meeting and function venue.

Science[edit]

Plant collections[edit]

The living plant collections include the Alpine and Rock Garden, Aquatic, Arboretum, Arid, Aroid, Bonsai, Bromeliad, Carnivorous Plant, Cycad, Fern, Grass, Island Flora, Mediterranean Garden, Orchid, Palm, Temperate Herbaceous, Tender Temperate, Tropical Herbaceous, and Tropical Woody and Climbers Collections.[80]

The Aquatic Garden is near the Jodrell laboratory. The Aquatic Garden, which celebrated its centenary in 2009, provides conditions for aquatic and marginal plants. The large central pool holds a selection of summer-flowering water lilies and the corner pools contain plants such as reed mace, bulrushes, Phragmites and smaller floating aquatic species.[81]

The Bonsai Collection is housed in a dedicated greenhouse near the Jodrell laboratory.[82]

The Arid Collection (including Cactaceae and many other succulent plants) is housed in the Tropical Nursery, the Princess of Wales Conservatory and the Temperate House.[83]

The Carnivorous Plant collection is housed in the Princess of Wales Conservatory.[84]

The Grass Garden was created on its current site in the early 1980s to display ornamental and economic grasses; it was redesigned and replanted between 1994 and 1997. Over 580 species of grasses are displayed.[85]

The Orchid Collection is housed in two climate zones within the Princess of Wales Conservatory. To maintain an interesting display the plants are changed regularly so that those on view are generally flowering. The Rock Garden, originally built of limestone in 1882, is now constructed of Sussex sandstone from West Hoathly, Sussex. The rock garden is divided into six geographic regions: Europe, Mediterranean and Africa, Australia and New Zealand, Asia, North America, and South America. There are currently 2,480 different "accessions" growing in the garden.[86]

The Arboretum, which covers the southern two-thirds of the site, contains over 14,000 trees of many thousands of varieties.[87]

Herbarium[edit]

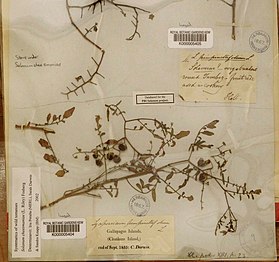

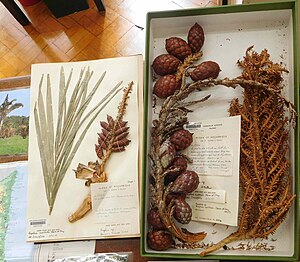

The Kew Herbarium is one of the largest in the world with approximately 7 million specimens used primarily for taxonomic study. The herbarium is rich in types for all regions of the world, especially the tropics, and is currently growing with 30,000 new specimen additions annually through international collaborations. The Kew Herbarium is of global importance, attracting researchers from and supporting and engaging in the science of botany all over the world, especially the field of biodiversity. A large part of the herbarium has been digitised,[88] and is available to the general public on-line.[89][90] The Index Herbariorum code assigned to the Kew herbarium is K[91] and it is used when citing housed specimens.

-

Kew Herbarium old wing

-

Kew Herbarium, storage in the old wing

-

Solanum cheesmaniae Kew herbarium sheet prepared by Charles Darwin, Chatham Island, Galapagos, September 1835

-

Kew Herbarium pressed and boxed specimens of Raphia australis

Kew Gardens holds further collections of scientific importance including a Fungarium (for fungi), a plant DNA bank and a seed bank.[89] The Kew Fungarium houses approximately 1.25 million specimens of dried fungi.[92]

Library and archives[edit]

The Library, Art & Archives at Kew are one of the world's largest botanical collections,[93] with over half a million items, including books, botanical illustrations, photographs, letters and manuscripts, periodicals, and maps. The Archives, Illustrations, Rare Book collections, Main Library, and Economic Botany Library are housed within the Herbarium building.

Owing to an agreement signed in 1962,[94] the scope of the collection generally does not overlap that of the Natural History Museum in London,[95] which concerns itself with the flora of Europe and North America.

Forensic horticulture[edit]

Kew provides advice and guidance to police forces around the world where plant material may provide important clues or evidence in cases. In one famous case, the forensic science department at Kew was able to ascertain that the contents of the stomach of a headless corpse found in the river Thames contained a highly toxic African bean.[96]

Economic Botany[edit]

The Sustainable Uses of Plants Group (formerly the Centre for Economic Botany), focuses on the uses of plants in the United Kingdom and the world's arid and semi-arid zones. The center is also responsible for the curation of the Economic Botany Collection, which contains more than 90,000 botanical raw materials and ethnographic artifacts, some of which are on display in the Plants + People exhibit in Museum No. 1. The centre is now located in the Jodrell Laboratory.[97]

Jodrell Laboratory[edit]

Named after a scientific benefactor, Thomas J. Phillips Jodrell, the Jodrell laboratory was established in 1876 by Kew’s Director Joseph Dalton Hooker and his Assistant William Turner Thiselton-Dyer as a base for researchers in disciplines including plant physiology, anatomy and embryology, fossil botany and mycology.[98][99][100] It represents one of the world’s first non-university affiliated laboratories and is the location for early discoveries on living and fossil plants. Initially built as a small single-storey laboratory, the original Jodrell building was replaced by a larger building in 1965 and subsequently extended by the addition of the Wolfson Wing in 2006.

The celebrated botanist Dukinfield Henry Scott was Assistant Keeper of the Jodrell Laboratory from 1892 to 1906. Resident and visiting researchers during that time included the structural botanists Ethel Sargant and Wilson Crossfield Worsdell, the cell biologist Walter Gardiner, the marine biologist Felix Eugen Fritsch, the physiologist Joseph Reynolds Green and the palaeobotanists William Henry Lang and Frederick Orpen Bower.

Subsequently, the Jodrell Laboratory was established as a centre for systematic botany by the plant anatomist Charles Russell Metcalfe, Keeper of the Jodrell Laboratory from 1930 to 1969, and his successors, the cytogeneticists Keith Jones (1969-1987) and Michael David Bennett (1987-2006).

The Jodrell Laboratory has spawned other laboratories and institutes, including the Laboratory of Plant Pathology in Harpenden (1920), the Imperial Bureau of Mycology in Kew (1930) and the Millennium Seed Bank, which initially relocated to Kew’s Wakehurst Place in 1993 as the Physiology Section.

Achievements[edit]

The world's smallest water-lily, Nymphaea thermarum, was saved from extinction when it was grown from seed at Kew, in 2009.[101][102]

In 2022, Kew Gardens scientists identified a new species of Victoria waterlily, Victoria boliviana, that had been growing at the Gardens for over 170 years.[103]

Other features[edit]

Kew Constabulary[edit]

The gardens have their own police force, Kew Constabulary, attested under section 3 of the Parks Regulation Act 1872.[104] Formerly known as the Royal Botanic Gardens Constabulary, it is a small, specialised constabulary of two sergeants and 12 officers,[105] who patrol the grounds in a marked silver car. The Parks Regulation Act gives them the same powers as the Metropolitan Police within the land belonging to the gardens.[106][107]

War memorials[edit]

The memorial to the several Kew gardeners killed in the First World War lies in the nearby St Luke's Church in Kew. It was designed by Sir Robert Lorimer in 1921.[108]

There are two memorial benches in the gardens. The Remembrance and Hope seat and the Verdun Bench, both containing parts of a felled oak tree whose acorn came from the battlefield of Verdun. The oak was grown at Kew until a storm in 2013 damaged the tree and so required removal.

Food and Drink[edit]

Kew is home to a number of eateries including The Orangery, Pavilion Bar and Grill, The Botanical Brasserie and Victoria Plaza Café.[109]

In 2021, the new Family Kitchen & Shop opened near the Children's Garden, replacing the nearby tented White Peaks Family Restaurant.[110]

Media[edit]

Films, documentaries and other media made about Kew Gardens include:[111]

- A short colour film World Garden by cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth in 1942[112]

- A 2003 episode of the Channel 4 TV series Time Team, presented by Tony Robinson, that searched for the remains of George III's palace[113]

- A 2004 episode of the BBC Four series Art of the Garden which looked at the building of the Great Palm House in the 1840s[114]

- BBC website: A Year at Kew — a 2005 documentary of "behind the scenes" at Kew Gardens

- Three series of A Year at Kew (2007), filmed for BBC television and released on DVD[115]

- Cruickshank on Kew: The Garden That Changed the World, a 2009 BBC documentary, presented by Dan Cruickshank, exploring the history of the relationship between Kew Gardens and the British Empire[116]

- David Attenborough's 2012 Kingdom of Plants 3D[117]

- 2014 video game Sherlock Holmes: Crimes & Punishments featured an episode The Kew Gardens Drama which centers on a murder in the building.[118]

In 1921 Virginia Woolf published her short story "Kew Gardens", which gives brief descriptions of four groups of people as they pass by a flowerbed.[119][120]

Access and transport[edit]

.jpg/220px-Kew_Gardens%2C_London_Borough_of_Richmond_upon_Thames%2C_TW9_(3039724552).jpg)

Kew Gardens is accessible by four gates that are open to the public: the Elizabeth Gate, at the west end of Kew Green, and was originally called the Main Gate before being renamed in 2012 to commemorate the Diamond Jubilee of Elizabeth II;[121] the Brentford Gate, which faces the River Thames; the Victoria Gate (named after Queen Victoria), situated in Kew Road, which is also the location of the Visitors' Centre; and the Lion Gate, also situated in Kew Road.[122]

Other gates that are not open to the public include Unicorn Gate, Cumberland Gate and Jodrell Gate (all in Kew Road), Isleworth Gate (facing the Thames), and Oxenhouse Gate (south boundary with Old Deer Park).[60]

Kew Gardens station, a London Underground and National Rail station opened in 1869 and served by both the District line and the London Overground services on the North London Line, is the nearest train station to the gardens – only 400 metres (1,300 ft) along Lichfield Road from the Victoria Gate entrance.[123] Kew Bridge station, on the other side of the Thames, 800 metres from the Elizabeth Gate entrance via Kew Bridge, is served by South Western Railway from Clapham Junction and Waterloo.[123]

London Buses route 65, between Ealing Broadway and Kingston, stops near the Lion Gate and Victoria Gate entrances; route 110, between Hammersmith and Hounslow, stops near Kew Gardens station; while routes 237 and 267 stop at Kew Bridge station.[123]

London River Services operate from Westminster during the summer, stopping at Kew Pier, 500 metres (1,600 ft) from Elizabeth Gate.[123] Cycle racks are located just inside the Victoria Gate, Elizabeth Gate and Brentford Gate entrances. There is a 300-space car park outside Brentford Gate, reached via Ferry Lane, as well as some free, though restricted, on-street parking on Kew Road.[123]

See also[edit]

- List of World Heritage Sites in the United Kingdom

- Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, which manages Kew Gardens and Wakehurst Place

- Wakehurst Place

- Botanists active at Kew Gardens

- Joseph Dalton Hooker, who succeeded his father as director in 1865

- The Great Plant Hunt – a primary school science initiative created by Kew Gardens, commissioned and funded by the Wellcome Trust

- Index Kewensis, a massive index of plant names started and maintained by Kew Gardens

- Kew Bulletin, a quarterly peer-reviewed scientific journal on plant and fungal taxonomy published by Springer Science+Business Media on behalf of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

- The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. An illustrated guide. Third Edition. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1959.

References[edit]

- ^ "Kew's scientific collections – Kew". www.kew.org. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ "Living collections at Kew". Kew.org.

- ^ "Science collections at Kew". kew.org.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Most visited attractions in London UK 2021". Statista. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Dyduch, Amy (28 March 2014). "Dozens of jobs at risk as Kew Gardens faces £5m shortfall". Richmond Guardian. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew". World Heritage. UNESCO. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ^ "Kew, History & Heritage" (PDF). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2008. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ^ "Director of Royal Botanic Gardens". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 14 October 2010. Archived from the original on 15 March 2007. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ Historic England (1 October 1987). "Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (1000830)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ "Quiz: Are you a Kew history buff?". Kew Gardens. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d Malden, H E (1911). Kew, A History of the County of Surrey: Volume 3. pp. 482–487.

- ^ Lysons, Daniel (1792). The Environs of London: volume 1: County of Surrey. pp. 202–211.

- ^ "London Attractions and Places of Interest Index". milesfaster.co.uk.

- ^ Harrison, W (1848). The Visitor's Hand-book to Richmond, Kew Gardens, and Hampton Court. Cradock and Company. p. 25.

- ^ Parker, Lynn; Ross-Jones, Kiri (13 August 2013). The Story of Kew Gardens. Arcturus Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 9781782127482.

- ^ Jones, Martin. "Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Wakehurst Place". infobritain.co.uk. Archived from the original on 17 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ UNESCO Advisory Body (2003). UNESCO Advisory Body Evaluation Kew (United Kingdom) No 1084 (PDF) (Report). UNESCO.

- ^ Drayton, Richard Harry (2000). Nature's Government: Science, Imperial Britain, and the 'Improvement' of the World. Yale University Press. p. 78. ISBN 0300059760.

- ^ The Epicure's Almanack, Longman, 1815, pages 226–227.

- ^ Smith, R G (1989). Stubbers: The Walled garden.

- ^ Jarrell, Richard A. (1983). "Masson, Francis". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. V (1801–1820) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ "Lancelot 'Capability' Brown (1716–1783)". Kew History & Heritage. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ^ Lankester Botanical Garden (2010). "Biographies" (PDF). Lankesteriana. 10 (2/3): 183–206, page 186. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Palm House and Rose Garden". Visit Kew Gardens. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ The Crystal Palace was an even more imposing glass and iron structure but a fire destroyed it.

- ^ "Suffragists burn a pavilion at Kew; Two Arrested and Held Without Bail – One Throws a Book at a Magistrate". The New York Times. 21 February 1913.

- ^ Bone, Victoria (16 October 2007). "Kew: Razed, reborn and rejuvenated". BBC News. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ "Kew Gardens Flagpole". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (3 May 2018). "'Breathtakingly beautiful': Kew's Temperate House reopens after revamp". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ "Celebrating the tree". Kew blog. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ "Treasures of London – The 'Old Lion' Maidenhair Tree, Kew Gardens". exploring-london.com. 4 February 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ "Treetop Walkway". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ Rose, Steve (9 October 2017). "David Marks obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 October 2017 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ "Treetop Walkway". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "The making of the Treetop Walkway". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 7 June 2008. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ a b "Lake and Crossing". Kew. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "Lake and Sackler Crossing". Kew. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Maps of Kew Gardens". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 20 October 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Correspondent, Louise Jury, Chief Arts (13 April 2012). "New St Pancras wins major award for architecture". Evening Standard. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Kew Garden set to bee a permanent home for popular sculpture The Hive". Evening Standard. 24 April 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ "Kew Explorer land train". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Compost heap". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Compost heap". Visit Kew Gardens. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ "Introduction to the Gardens". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 4 July 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Aroid House No 1 listing".

- ^ "Visit Kew Gardens – The Orangery". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 3 May 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ a b Kohlmaier, Georg and von Sortory, Barna. Houses of Glass, A Nineteenth-Century Building Type. The MIT Press, 1990 (p300)

- ^ Kohlmaier, Georg and von Sortory, Barna. Houses of Glass, A Nineteenth-Century Building Type. The MIT Press, 1990 (p140)

- ^ a b c Kohlmaier, Georg and von Sortory, Barna. Houses of Glass, A Nineteenth-Century Building Type. The MIT Press, 1990 (p296)

- ^ Kohlmaier, Georg and von Sortory, Barna. Houses of Glass, A Nineteenth-Century Building Type. The MIT Press, 1990 (p299)

- ^ "Local Sculptures – 10 Queen's Beasts". Brentford Dock Residents. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ Historic England. "CAMPANILE, Richmond upon Thames (1251642)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Augusta, Princess of Wales Archived 20 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 6 October 2005.

- ^ Secrets of the Princess of Wales Conservatory, Kew Gardens, retrieved 14 September 2021

- ^ a b The History of the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew

- ^ "Temperate House, Royal Botanic Gardens". Donald Insall Associates. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ "Waterlily House". Visit Kew Gardens. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ Historic England (9 May 2011). "Australian House Kew (1401475)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d The Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, Key Plan, 1974

- ^ Morley, James (1 August 2002). "Kew, History & Heritage". Kew. Archived from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ "Dragons to return to The Great Pagoda at Kew after 200-year hunt". Historic Royal Palaces. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ "'Japan 2001′ fest set to take center stage in U.K." The Japan Times. 15 February 2001. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ "Queen Charlotte's Cottage". Historic Royal Palaces. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ^ Historic England. "King William's temple (1251785)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Historic England. "Temple of Aeolus (1262669)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Mcewen, Ron (2018). "Solving the Mysteries of Kew's Extant Garden Temples". Garden History. 46 (2): 196–216. JSTOR 26589606. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "Temple of Arethusa (1251777)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Historic England. "Temple of Bellona (1262581)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Historic England. "Ruined Arch (1251956)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Historic England. "Ice House (1251799)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ^ "Kew Palace". Donald Insall Associates. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ "Kew Gardens Sundial". Public Monuments and Sculpture Association. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ "Thomas Tompion (bapt.1639 d. 1713) – Sundial". www.royalcollection.org.uk. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ "Medical Museums". medicalmuseums.org. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ^ "Marianne North Gallery, Royal Botanic Gardens". Donald Insall Associates. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Wood collection at Kew".

- ^ "Cambridge Cottage". Heritage Gateway.

- ^ Historic England. "Cambridge Cottage (1065396)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ "Plants". Kew Gardens. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "Aquatic Collection". Kew Gardens. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "Bonsai Collection". Kew Gardens. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "Arid Collection". Kew Gardens. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "Carnivorous Plant Collection". Kew Gardens. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "Grass Collection". Kew Gardens. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "Orchid Collection". Kew Gardens. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "Arboretum". Kew Gardens. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "Kew Herbarium Catalogue". Archived from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Kew website, Herbarium Collections". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ "Welcome to the Kew Herbarium Catalogue". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ "Index Herbariorum". Steere Herbarium, New York Botanical Garden. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ "The Fungarium" Archived 10 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved March 2020

- ^ "Kew's Library" Archived 15 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. Retrieved March 2020

- ^ "The Library | Kew". www.kew.org. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ Fortey, Richard (2008). Dry Store Room No. 1. HarperCollins. ISBN 9780007209880.

- ^ "Jodrell Laboratory". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ "Economic Botany Collection". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Metcalfe, C R (1976). Jodrell Laboratory Centenary 1876–1976. Royal Botanic Gardens Kew.

- ^ Thiselton-Dyer, W. T. (November 1910). "The Jodrell Laboratory at Kew". Nature. 85 (2143): 103–104. doi:10.1038/085103d0.

- ^ Rudall, Paula J. (December 2022). "From "New Botany" to "New Systematics": an historical perspective on the Jodrell Laboratory". Kew Bulletin. 77 (4): 807–818. doi:10.1007/S12225-022-10061-0.

- ^ Ghosh, Pallab (18 May 2010). "Waterlily saved from extinction". BBC News. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ^ Magdalena, Carlos (November 2009). "The world's tiniest waterlily doesn't grow in water!". Water Gardeners International. 4 (4). Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ^ Brewer, G. (2022, July 4). "Uncovering the giant waterlily: A botanical wonder of the world." Archived 2022-07-04 at the Wayback Machine Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. Retrieved January 20, 2023

- ^ "Parks Regulation Act 1872". Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ McCarthy, Michael (30 January 2001). "How many policemen does it take to guard an orchid?". The Independent.

- ^ "Parks Regulation Act 1872: 3 Definition of "park-keeper" Section 3". www.legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ "Parks Regulation Act 1872: 7 Powers, duties, and privileges of park-keeper". www.legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ Dictionary of Scottish Architects: Robert Lorimer

- ^ "Eating and drinking | Kew". www.kew.org. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Adam, Whittaker (15 December 2021). "Lumsden & Mizzi serve up new Kitchen & Shop for Kew". Blooloop. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ "Videos". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ "World Garden". British Council Film Collection. The British Council. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "IMDb: Time Team: Season 10, Episode 9 Kew Gardens, London". IMDb.com. 2 March 2003.

- ^ "IMDb: Art of the Garden: Season 1, Episode 2 The Great Palm House at Kew". IMDb.com. 4 June 2004.

- ^ "A Year at Kew". Episode guide. BBC. 2007. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ "BBC Two: Cruickshank on Kew: The Garden That Changed the World". BBC. 10 December 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ "Kew: Kingdom of Plants with David Attenborough". Kew.org. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Maria, Charlene (17 January 2022). "Sherlock Holmes: Best Murder Cases In The Series, Ranked". TheGamer. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Reid, Panthea (2 December 2013). "Virginia Woolf: early fiction". Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 2. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ Woolf, Virginia (1921). Kew Gardens.

- ^ "Royalty opens Kew Gardens' Elizabeth Gate". Richmond and Twickenham Times. 21 October 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ "Which gate to use". Visit Kew Gardens. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Getting here". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 767. — The Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew originated in.....

- 1759 establishments in England

- Buildings and structures completed in 1759

- Art museums and galleries in London

- Botanical gardens in London

- Botanical research institutes

- Buildings and structures on the River Thames

- Gardens by Capability Brown

- Gardens in London

- Greenhouses in the United Kingdom

- Grade I listed buildings in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

- Grade I listed parks and gardens in London

- Grade II listed buildings in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

- Japanese gardens in England

- Kew Green

- Kew, London

- Medical museums in London

- Museums in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

- Natural history museums in England

- Parks and open spaces in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

- Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

- World Heritage Sites in London

- Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha